Author

We were delighted to welcome Dr David Horsell, experimental physicist and senior lecturer at The University of Exeter, to host our recent Michelmores IQ event focusing on Graphene − a new miracle in the material world. But why exactly has graphene been dubbed a ‘miracle material’ and why is Britain investing £60m to develop it? We caught up with Dr Horsell, to find out more.

Q – What is Graphene?

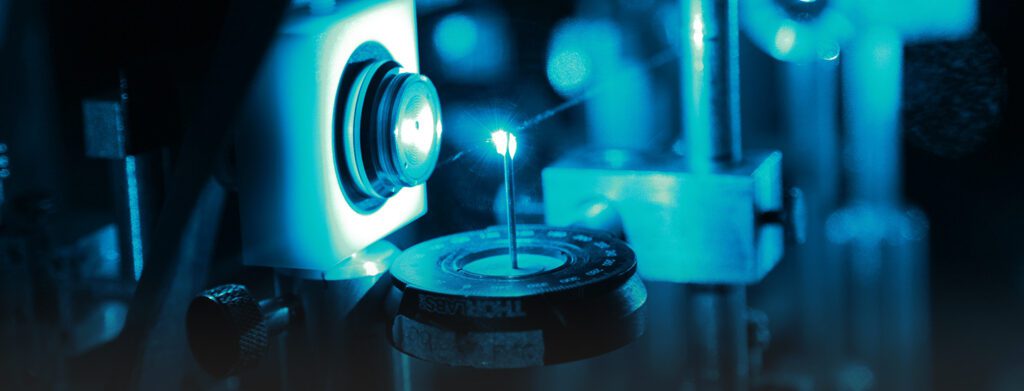

A – Put simply, graphene is a single layer of graphite − an atomically thin sheet of carbon. Whilst scientists have theorised about graphene for a long time, researchers at Manchester University demonstrated that it could indeed become a reality, when it was produced in the lab in 2004.

Carbon comes in various forms and some of these have been known about for a very long time, such as diamond (pure carbon) and graphite (layers of carbon). But graphene, a perfect monolayer of graphite, presented a very exciting new material with great potential.

Q – What makes Graphene so exciting?

A – Coming across new materials is nothing new for scientists, and in the latter half of the 20th Century, there have been many significant material discoveries, including carbon nanotubes and buckminsterfullerene. The common problem however, is finding useful commercial applications for these new materials.

Graphene however, is the only two-dimensional conducting membrane in existence. It is transparent, strong, flexible, stretchable and impermeable – a collection of very useful qualities when it comes to potential commercial applications. And it’s this combination of material properties that is so exciting, for both academia and industry.

Q – Without being too technical, how was Graphene discovered?

A – Graphene is simply a single layer of graphite, and because the structure of graphite is easily pulled apart, it is possible to peel off the layers one by one. Believe it or not, in the early days, this was done using sellotape from the stationary cupboard, to peel off each layer.

Q – How did the University of Exeter get involved with Graphene?

A − At the time graphene was discovered at Manchester University, Exeter researchers were focusing on a range of other materials, such as carbon nanotubes. It wasn’t until 2005 (shortly after its discovery) that we started researching graphene seriously, but we were still amongst the first universities in the world to study it.

Q – Where can we find Graphene?

A − A number of companies are now experimenting with man-made versions of Graphene.

There are two main ways to make Graphene, chemical vapour deposition and epitaxial growth, but a number of research groups are currently looking at new ways. Amazingly, you can now buy graphene online from companies such as Graphene Supermarket, who will even send it to you in the post!

Graphene isn’t yet being used on a mass scale, for a few reasons. One reason being that whilst it’s a brilliant conductor, it’s almost too good a conductor and is almost metallic in its qualities. One of our biggest challenges at the moment is to find out how to make it not conduct quite so well for applications in electronics where conductions needs to be finely controlled.

Another big consideration is its chemical stability and of course the health and safety aspects of using a brand new material in every day products.

Q – Can you give us a few examples where Graphene might be used in everyday items?

A − There are so many possibilities, but one example includes the mobile phone screen – a big part of many of our lives. Most phone screens are currently made from a material called indium tin oxide which is very expensive, so graphene with its transparent, conducting and strong qualities could be a great substitute, and much cheaper replacement for the millions of mobile phones made each year.

Another important application is in creating highly sensitive medical sensors. The conduction in graphene has been found possible to be controlled by any biological material that interacts with it, opening up the possibility to create tiny electronic sensors from it that could be used to detect trace chemical markers of disease in the human body.

A quite different application would be to use its strength and flexibility to make new materials for the construction industry. So you can see that graphene could end up in quite unexpected products in the future.

Q – Graphene was discovered in the UK, but are we still leading the way in its development?

A – According to a recent report by Cambridge University, there has been a huge increase in the patent applications of graphene. However, despite the initial discovery being made here, the number of patents is now much higher in China, America and South Korea.

I suspect that the first industrial applications might be in the Far East and America but Europe is trying to catch-up. The EU recently announced plans to invest £1 billion in the development of graphene over the next 10 years, across various companies and research centres. And alongside this investment, we might well see closer links between research centres and commercial industries.

Q – When do you think we will see products made with Graphene on our shelves, on a large scale?

A – Typically, the path to market with any new material is 20 years or more − so ten years on from its discovery in 2004, we’re not doing too badly at all. There are lots of prototypes out there already, but it will probably be another 10 years until we see graphene used on an industrial scale.

Thanks again to Dr David Horsell, for leading such an informative and forward-thinking event.

For information on the next Michelmores IQ event, please visit our events page or contact Saskya Liney, Events Coordinator via email at Saskya.liney@michelmores.com or by telephone on 01392 687655.