Jalla and another -v- Shell International Trading and Shipping Co Ltd and another (“Jalla”)

The tort of private nuisance has received significant judicial attention from the U.K. Supreme Court in 2023. The judgment in Fearn v Board of Trustees of the Tate Gallery (“Fearn”) [2023] UKSC 4 was given on 1 February 2023. Fearn clarified that intrusive viewing from a neighbouring property (in that case the Blavatnik Building, part of the Tate Modern art museum in London) into residential flats, can in principle (and did in that case) give rise to a claim for private nuisance.

Following Fearn, the Supreme Court, in Jalla, has provided authority on the circumstances in which a private nuisance is continuing and constitutes a ‘continuing cause of action’, a concept which has implications for the limitation period (the length of time potential claimants have to bring a claim).

This article examines:

- what the tort of private nuisance is;

- the concept of the continuing cause of action and its impact upon the limitation period; and

- the implications of the Supreme Court judgment in Jalla.

Background: what is private nuisance?

The tort of private nuisance is committed: “where the defendant’s activity, or a state of affairs for which the defendant is responsible, unduly interferes with (or, as it has commonly been expressed, causes a substantial and unreasonable interference with) the use and enjoyment of the claimant’s land“[1].

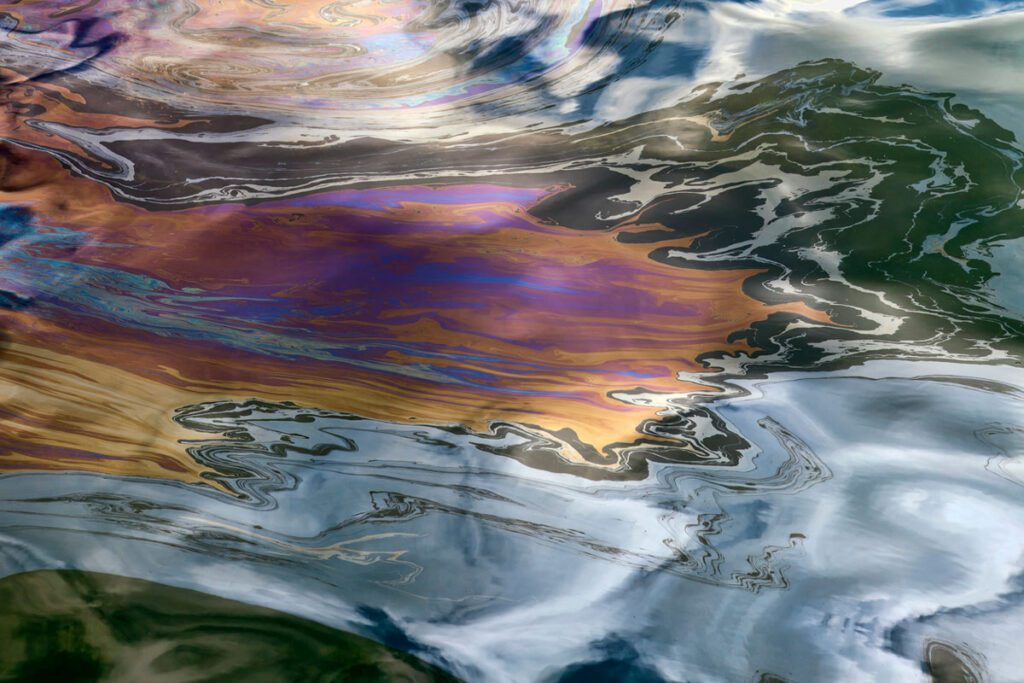

There is considerable scope for private nuisance claims to be brought and such potential claims may relate to (amongst others): odour, noise, intrusive viewing (as in Fearn), Japanese knotweed, tree roots, and environmental damage including oil spills such as in Jalla.

Jalla: the facts

In Jalla, the private nuisance claim arose from a major oil spill brought against a company within the Shell PLC group of companies. Despite the incident occurring in Nigeria, Jalla represents a further example of multinational companies being sued in the jurisdiction of England and Wales for oil spills. For further analysis of this trend, please see Michelmores’ article here: Liability for MNE’s in environmental law

The oil spill in Jalla was caused by an oil leak during operations at an offshore installation in an oil field which occurred off the coast of Nigeria in December 2011. The oil leak was stopped within six hours. This is an important point in categorising the incident as a one-off, rather than a continuing event, which will be revisited later in the article.

The claimants’ case was that the oil had not been removed or cleaned up and was continuing to cause them a private nuisance by reason of undue interference and enjoyment of their land.

Limitation Issues: the claim

The claimants issued their claim form in December 2017. The relevance of this is that in the jurisdiction of England and Wales, pursuant to S2 Limitation Act 1980, generally a claimant has six years from the date of the cause of action to bring a claim. Therefore, the claimants had no initial issue with limitation having issued their claim within time.

However, In April 2018 (beyond six years after the spill) the claimants attempted to amend their claim form and particulars of the claim.

The claimants argued that the claim constituted a continuing cause of action and, on that basis, that their amendments were not outside of a relevant limitation period and should be allowed.

The defendants resisted the application on the basis that the amendments were sought after the expiry of the limitation period and the claimants had to satisfy the requirements of the Civil Procedure Rules (“CPR”) relating to amending a statement of case outside a limitation period[2].

What is a continuing nuisance and why is it relevant?

At paragraph 26 of the judgment, the Judge described a continuing cause of action as follows (emphasis added):

“In principle, and in general terms, a continuing nuisance is one where, outside the claimant’s land and usually on the defendant’s land, there is repeated activity by the defendant or an ongoing state of affairs for which the defendant is responsible which causes continuing undue interference with the use and enjoyment of the claimant’s land. For a continuing nuisance, the interference may be similar on each occasion but the important point is that it is continuing day after day or on another regular basis. So, for example, smoke, noise, smells, vibrations and, as in Fearn, overlooking are continuing nuisances where those interferences are continuing on a regular basis. The cause of action therefore accrues afresh on a continuing basis.”

The relevance of a set of facts constituting a continuing cause of action is that the limitation period runs afresh from day to day. Had the Court found the facts of Jalla to constitute a continuing cause of action, the claimants’ proposed amendments to their claim would not face a limitation issue. More generally, the continuing cause of action concept means that, in circumstances constituting a continuing cause of action, a defendant committing a private nuisance continues to face litigation exposure even after six years has passed following the original incident.

The key issue for the Supreme Court to decide in Jalla was whether a one-off oil spill could constitute a continuing cause of action on the basis that the oil had allegedly not been cleaned up.

The Findings

The Judge summarised the claimants’ submissions as follows: “The essence.. is that there is a continuing nuisance in this case because, on the facts that are to be assumed for the purposes of this appeal, the oil is still present on the claimants’ land and has not been removed or cleaned up[3].”

Developing the point, the Judge illustrated the practical consequences of the claimants’ case on what constitutes a continuing cause of action by the following example: if a claimant’s land was flooded by an isolated incident on day one, if the land remained flooded on day 1000 there would be a fresh cause of action accruing day by day.

The Judge described the claimants’ submission as incorrect and found there to be no continuing cause of action in Jalla as to accept the claimants’ conception of a continuing cause of action that would undermine the law on limitation of actions. In coming to this finding, the Judge noted that: “there was no repeated activity by the defendants or an ongoing state of affairs for which the defendants were responsible that was causing continuing undue interference with the use and enjoyment of the claimants’ land[4]“. The Judge distinguished the one-off oil spill in Jalla with the example of a tree roots case which “provides a good example of a continuing nuisance…. In such a case, there is an ongoing state of affairs outside the claimant’s land, constituted by the living tree and its roots, for which the defendant is responsible and which causes, by extraction of water through its encroaching roots, continuing undue interference with the claimant’s land. The cause of action for the tort of private nuisance therefore accrues afresh from day to day“[5].

The Implications

The distinction between one-off events and events constituting a continuing nuisance have significant implications for the limitation period, with the former type of claims having to be brought within six years of the event and the latter type accruing a fresh cause of action for each day the nuisance is continuing (meaning that the limitation period extends). Those operating in sectors which may give rise to potential nuisance claims should take note of the requirement of “repeated activity or an ongoing state of affairs” required for a set of facts to constitute a continuing cause of action (in addition to the general nuisance requirements including causing undue interference with a potential claimants’ enjoyment of the land).

[1] Paragraph 2, Jalla v Shell [2023] UKSC 16: https://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKSC/2023/16.html

[2] CPR rr 17.4.

[3] Paragraph 34, Jalla v Shell [2023] UKSC 16

[4] Paragraph 37, ibid

[5] Paragraph 30, ibid